BY LETTER

Project Frontier

History > 0030 to 0900 AT: Solsys Era > 130 to 400 AT: The Interplanetary Age

Culture and Society > Cultural Factors > Interstellar Colonization

Project Frontier represented Terragens' first step towards becoming an interstellar civilization. A highly ambitious and groundbreaking project for its time, it marked the beginning of a new chapter in Terragen history with the development of several key technologies for interstellar spaceflight. However, the strategy that it employed ultimately caused the loss of the Alpha Centauri system, stymied a number of similar projects, highlighted the risks of the use of unsupervised AIs, and gave rise to the independent Neumann civilization known as the Nauri.Culture and Society > Cultural Factors > Interstellar Colonization

Background

Terragen civilization's first serious attempt at interstellar colonization began with none other than the nearest star system to Sol, Alpha Centauri. The system consists of three stars; the brighter two, Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman, form a close-in pair, distantly orbited by a much smaller red dwarf star known as Proxima Centauri. The major objects and structures within the system had been mapped via long range observations starting in the Information Age, and by 100 AT, the system was already known to be a decently resource-rich system suitable for colonization.Still, it was not until the 120s AT that the technological and industrial capabilities of the most advanced nation-states and largest corporations reached the point where the possibility of sending unmanned probes to the nearest stars was actually within reach. Earlier projects were hampered by unrealistic goals, lack of funding, technical difficulties, or legal disputes; none of them succeeded.

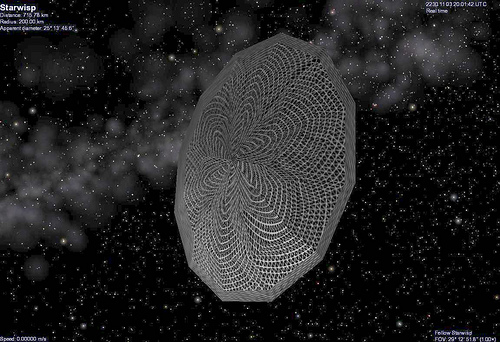

Image from Steve Bowers | |

| The Starwisp, the first successful interstellar probe to any destination, reached Alpha Centauri in 202 AT | |

Eventually, Terragen dreams of successful interstellar flight manifested in the form of the Starwisp Project, which used a massive maser array placed on the surface of Luna to accelerate a group of simple, lightweight flyby probes up to 0.07c. These probes passed by the trinary system starting in 202, producing images of various objects with sufficient resolution for researchers back at Sol to glean preliminary information on their planetology and locate the most obvious resource deposit candidates.

However, as successful as the effort to send flyby probes had been, it would be another matter altogether to decelerate and enter the system. The project to build such a probe would be a huge one, given the primitive state of various vital technologies at the time. Fortunately, the treasure trove of data and pretty pictures returned from the Starwisp probes generated a high level of public support for interstellar colonization, and several nations came together to provide funding for promising proposals. A contract was finally awarded to a consortium of 25 companies, including Acevedo, Artemis Development, Drextech, Fourneau Microbots, Jinyun Astronautic Technology, Hindustan Aerospace, Mitsubishi, the newly privatised NASA Exploration Corporation, Obatala, and Tilahun Biotech, each of which would handle different aspects of the project. Thus, Project Frontier was established.

The Project

Project Frontier was incredibly ambitious (or foolhardy depending on who was asked) for the time period. The project consisted of a number of probe launches with each probe fitted with a neumann factory. The probes would be accelerated by a powerful boostbeam, and decelerated by a combination of magbrake and fusion rocket. Upon arrival, these factories would be assembled and fed with raw resources in order to produce swarms of worker bots and more complex manufacturing tools. Later probes would arrive with more specialised equipment to accelerate the development of a local economy. If all went to plan, within a matter of years a sophisticated industrial base would be present with established communication stations, boostbeam relays, solar energy constellations, and nascent habitats ready to receive colonists. Designing an industrial seed small enough to be distributed among a fleet of probes was a daunting task. The project compensated for this by developing a series of flexible AI models that would run operations in the Alpha Centauri system. Unlike other AI in use in the Solar System, these designs were intended to operate for decades without human supervision, adapting and innovating as local conditions demanded.Initially, all went according to plan; launched in 221, and accelerating to almost a tenth of the speed of the light, the probes reached Alpha Centauri in 283, and the construction swarms manufactured by them quickly set up mining operations and factories on a number of objects within Rigil Kentaurus' asteroid belt. All the while, scientific data was being gathered and beamed back to the Sol System. While no signs of life were detected, the mission provided a wealth of valuable information about planetology in other star systems.

In 289 the project's mission control noticed the first signs of trouble. Several worker swarms started reporting disruptions to their logistics. Deliveries of raw resources and manufactured components began to arrive late, and in some cases to entirely the wrong facility. As this escalated more disturbing reports of bot behavior arrived; newly laid infrastructure built by one swarm was immediately dismantled by another, asteroid orbital adjustment lasers began contesting each other's actions (in one notable case causing an asteroid to fragment, becoming a shipping hazard), and by the summer of 289 video footage showed swarms using industrial explosives against each other.

It wasn't long before it was confirmed that the neumanns appeared to be splitting into at least two factions. Error reports from thousands of bots arrived flagging others as "unaligned in goals". Exactly what had prompted this was unclear, but the schism appeared to center around a drift in the AIs' pattern recognition of their consortium owners. Different interpretations of the swarm's true owners led to a cascade of conflicting goals.

Solsys could only watch as the methods each swarm used to restore order among their own workflows became increasingly violent, made evident by the rising number of reports of the demolition of various facilities by 'rogue elements', which were often accompanied by a corresponding report from swarms from another faction stating they had just destroyed a rogue facility that was hindering their own progress. Within 18 months, contact with the prevailing faction was mysteriously lost. Other factions were outcompeted; one by one they were either completely destroyed or vanished, and by the time the first response message from the Solar System reached Alpha Centauri, all contact with the neumanns was lost.

Initially it was not known what exactly caused the schism among the neumanns. Many experts analyzed the available data in order to explain the incident, giving rise to a number of competing theories. Many organizations, including several AI safety advocacy groups, called for on-site investigation of the Alpha Centauri system. This led to the launch of the Class R probes, a series of heavily weaponized and armored military-grade spacecraft, in 308. The Class R probes reported back in 365, having successfully arrived at Alpha Centauri. They discovered a thriving system-wide community of neumanns; clearly the aberrant machines had successfully established their own civilization in isolation from the Solar System. Acting on their own initiative, the Class R probes successfully penetrated the firewalls of two smaller factories, which evidently weren't expecting such an attack, in order to search for the exact cause of the failure. Soon after this, the local defense nodes determined the Class Rs to be a threat, mobilized, and overwhelmed the infiltrators.

The loss of Alpha Centauri bankrupted the consortium and severely reduced public enthusiasm for interstellar colonization - many similar projects that were in development at the time were defunded and canceled - but Project Frontier also played a vital role in raising concerns regarding the various risks associated with automated interstellar colonization, and provided invaluable information and experience for the next generation of colonization projects.

Legacy

As the very first interstellar mission that involved slowing probes, Project Frontier developed a large number of cutting edge technologies.Most intimately related to the nature of the project were the boostbeams - prior to Frontier, the most advanced boostbeam systems were either capable of accelerating multi-million-kilogram ships to interplanetary speeds, or kilogram-sized Starwisp probes to 0.07c. The boostbeam system that the Project Frontier probes demanded needed to be powerful enough to accelerate large probes and their payload up to interstellar-level speeds. The development of such a boostbeam system effectively marked a new era in interstellar spaceflight as the launch of probes capable of more than simply flying through the system became feasible. Some of the new technologies developed in the process also trickled down to existing interplanetary boostbeams, allowing faster missions to the further reaches of the Solar System as well as reducing the cost of travel, and speeding up the colonization and development of various destinations within the Solar System itself.

While not as spectacular as the boostbeams, the most important aspect of the probes was their ability to haul a miniaturized version of entire industries - the industrial seed - required to support the colonization effort. Fabricators were a brand new technology at the time, each one a gigantic masterpiece of human engineering. It was impractical to fit one inside a single probe, so the strategy was to distribute it among a number of probes, with some level of redundancy to prevent the loss of a single vessel from dooming the entire mission. This strategy was later adopted by many of the early interstellar probe missions, only becoming phased out as smaller and smaller fabricators became available.

Still, most modern historians agree that the most important legacy of this project lay in its failure, which highlighted the difficulty and risks of an automated interstellar colony mission. With the exact cause of the aberrant behaviors of the neumann swarms still inconclusive at the time, many attempts to explain the incident were formulated.

One theory stated that the neumanns themselves were to blame; as the tasks and the size of the swarm increased in complexity, so did the likelihood of the emergence of aberrant behaviors. This was already a point of concern that many experts and critics of the project had raised even during the development phase, and the loss of Alpha Centauri only served to further emphasize the inherent unpredictability of AIs. Analysis of data from the hacked factories that the Class R probes managed to transmit prior to being destroyed revealed no abnormalities indicative of outside interference, strongly supporting this hypothesis.

Another competing theory suggested that the failure was the work of terrorists or anti-colonisation saboteurs. There had been a number of high profile cases of sabotage and digital subversion of space-based infrastructure, though no single culprit was ever found. Historians speculate the involvement of early ahumans. Although no evidence supporting ahuman involvement in this particular incident has ever been found in the end, they were later proven to be behind the loss of a number of other interstellar probes, many of which simply disappeared in flight only for the descendants of the ahumans that hijacked them to be discovered at the destination by interstellar explorers later on.

In practice, most interstellar missions, both the few missions that survived the fiasco and those that emerged afterwards, would take precautions against a repetition of the Alpha Centauri failure. In more extreme cases, some projects opted to leave out the construction probes entirely, instead only sending a survey probe to scout the system prior to the launch of the colony ship. These probes provided information regarding the location of various resources within the destination system, and in some cases performed simple tasks, such as saturating the orbital space with microsats in order to establish a communication network. Other projects still utilized construction probes, but equipped with less capable AIs, which reduced the risk of them going rogue in exchange for the need for more massive industrial seeds. Some of these missions still failed, but many succeeded.

The loss of Alpha Centauri was followed by a period of intense research into AI safety and cybersecurity in order to minimize the possibility of rogue AI. The products of this effort greatly benefited many sectors, including the next generation of interstellar colonization projects.

The neumanns that went on to establish their own civilization at Alpha Centauri would later be called the Cenaurinume civilization by the sophonts of the First Federation. Their lineage became known as the Nauri.

Related Articles

Appears in Topics

Development Notes

Text by The Astronomer, Ryan B

Initially published on 27 August 2021.

Initially published on 27 August 2021.